- Home

- Patricia A. Smith

The Year of Needy Girls Page 13

The Year of Needy Girls Read online

Page 13

Deirdre turned and nodded.

“And—this is awkward—I normally don’t repeat gossip,” Beth Ann said, giving a little laugh. “I just hate gossip.” She exhaled and smiled.

Deirdre offered her a chair at the kitchen table, and waited for her to continue.

Beth Ann folded and unfolded her hands. “My daddy drilled it into me. No gossip, he always said. Good girls don’t. But it isn’t really gossip now, is it, if I tell it to you? I’m only reporting what has been said about you by others. Ms. Murphy—”

“Deirdre, please.” She turned down the heat under the chocolate.

“Oh, this is crazy,” Beth Ann said. “Why can’t I just say what I need to say?” She stood and paced. Fingered her pearls. “I don’t care.” She turned to face Deirdre after several moments. “I don’t believe it, but even so, I don’t care. I’ve seen the way you are with those girls and I don’t for one minute think you would do anything to harm them, I know you wouldn’t. I’m sorry you’ve been let go—”

“Beth Ann—”

“It’s ignorant.” Beth Ann blushed, crossed her arms. “I want to help. In any way I can.”

If Deirdre had expected anyone to show up, it was Forest. Or maybe even Evelyn. But here was Beth Ann in her soft pastel colors, pacing in her living room. And of course Deirdre wanted to know exactly what the women were saying—Frances Worthington especially—how they looked when they talked about her, with what kind of sneer or laugh. And if anybody seemed shocked. How many new parents were against her now? And what exactly was Frances telling everybody anyway? She waited for Beth Ann to give the details.

“You’ve got your ignorant element, Beth Ann, my daddy would say, and such people are not worth your while.”

“I would’ve liked your dad.” Deirdre stirred the chocolate with a spatula.

“Oh, he was—is—he’s still alive. He is a real gem. A Southern gentleman, truly.” Beth Ann pulled out a kitchen chair and sat on the edge. “Daddy—well, I didn’t come here to talk about my daddy.” She ran an index finger beneath her pearls.

“I appreciate you coming over.” Deirdre stirred. “I’m just sick about this.” She felt tears begin to pool. She swallowed and glanced over at Beth Ann, willed the tears not to fall.

“People will think what they think—”

“That’s what your daddy said?”

Beth Ann blushed. “But isn’t it the truth?” She shook her head and gave a little laugh. “People can think all they want that Southerners are backward. In the South, you grow up hearing about Yankee this, Northern that. When we’re little, we find out all the fancy, famous schools are up North too, like y’all are smarter? Now, Northerners might be more liberal, but less ignorant? The South does not have a monopoly on that.” She stood again. “Ms. Murphy, if you need anything, you call me, you hear?” She extended her hand.

Deirdre put down the spatula and shook her hand, then walked her to the front door. “Thanks for stopping by,” she said. “I really appreciate it.”

“Now, I mean it. You call. If you need anything.”

“I will,” Deirdre told her, and closed the door.

The brief moment of ease she had found while mixing the mousse had disappeared. She supposed Beth Ann was right: people would think what they wanted to think, and there wasn’t much she or anyone else could do about that. But it didn’t seem fair, that people who didn’t even know you might form an opinion based on a rumor—and worse, a rumor that wasn’t even true.

Well, there was no sense jumping to conclusions just yet. Deirdre didn’t know what people were thinking, and Beth Ann was a perfect example of someone she had never expected to have on her side. Why was it that you automatically thought the worst of people? Still, walking back to the kitchen, the dread turned her stomach sour—the desire to cook, to do anything, was gone. She scooped the egg whites into the melted chocolate, turned over handfuls of stiff egg whites with the spatula, folding each new bit into the chocolate, blending the two so that slowly, what was in the bowl turned a paler shade of brown and grew puffier and lighter. She worked on automatic, the repetitive motions calming the hysteria that was building in her chest. She spooned the mousse into six small ramekins. It would be like Forest to come by when school was over, when he was fairly certain SJ would be working. Deirdre scraped the side of the chocolate pan with a spoon and licked it. She glanced at the clock. School would be out in another half hour. And it had been several hours since she’d phoned SJ at the library. Deirdre put the ramekins into the fridge and dialed the library’s number.

“Bradley Public Library.”

“Sara Jane Edmonds, please.” The light in the kitchen had faded; now everything seemed to have turned a shade of gray. Outside the window, a breeze blew the yellowed leaves of the oak tree. A squirrel scampered across the phone line.

“Hello?”

“Hey.” Deirdre twisted the phone cord around her finger.

“Deirdre? I was expecting . . . I didn’t think it would be you.”

“You didn’t get my message?”

“Message? Oh, yeah. Yeah, but it was . . . Things were crazy here today. Listen, don’t count on me for dinner. I’m probably going to be late.”

“But I’m cooking! I’ve already started. It was supposed to be a surprise.” Before SJ could say anything, Deirdre added, “So officially? I’m on leave.”

“God, the meeting with Martin, I forgot. I’m sorry.” SJ sounded distracted and Deirdre heard her riffling through papers.

“Are you listening?”

SJ sighed.

“Forget it. Just come home, would you? We can eat dinner late,” Deirdre said. “Nine o’clock if you want.” She hung up.

So much for patching things up. SJ wasn’t even home yet and Deirdre was already mad at her. And vice versa, it sounded like. For the first time, she imagined the scenario through SJ’s eyes. How humiliating. Could you be the spouse of a child molester? How did those wives of embezzlers do it, appear on TV as if nothing their husbands had done was wrong? In private, did those women still love their husbands, or was it all for show only? Deirdre didn’t see how anyone could fake it like that—either you were still in love and supportive of your partner, or you weren’t. And maybe in their heart of hearts, those women believed in their husbands, believed that they hadn’t cheated at all and had been falsely accused, as Deirdre had been. How important it was for the husbands, Deirdre realized, to have someone who still believed in them. She rubbed at a spot of chocolate on the counter. No, she corrected herself, it wasn’t having someone; it was having a spouse.

Deirdre took the veal from the refrigerator. Damn SJ. She could have at least asked about the meeting with Martin Loring. She could have at least pretended that she wanted to know what had happened—her partner, for God’s sake. Deirdre wanted to be furious with SJ, but she wanted more to get things back to normal, to the way they were just before they moved into the new house. Already that seemed like ages ago, when in truth it had only been weeks. Deirdre didn’t even want to think about how they would afford the new house if she did get fired and no longer earned a paycheck. Maybe finances were part of the reason SJ was so mad and distant, but Deirdre doubted it. SJ never worried about finances.

It was actually one of the things she appreciated about SJ. Because SJ came from money, had always had enough growing up, and would, frankly, have enough for the rest of her life, she didn’t need to worry. Deirdre never knew that feeling. In her house, money had always been an issue. Her parents discussed it constantly. She loved the kind of easy confidence SJ had about money and brought to their life as a couple. She didn’t feel like she was entitled to any of SJ’s money, it wasn’t that, but just the air SJ had about finances not being an issue helped calm Deirdre’s own worries.

By now, the sun had moved almost completely to the front of the house. Deirdre poured herself another glass of chardonnay. What day was it? Monday. Nothing after school except sports practice. Forest might

be working late, getting organized with lesson plans. Every fall, both he and Deirdre resolved to be better organized, and they always started out eager and committed, their good efforts lasting until October, if they were lucky. Then, the usual overload got the best of them. They could never figure out how it happened—a special assembly, a field trip, a request by another teacher for additional class time, an all-grade project—any one of these was enough by itself to throw the schedule into disarray, and when the schedule was crazy, everybody felt it. Deirdre never understood how a simple rearranging of classes could have such an adverse impact on everybody, on their moods, their ability to be organized, their productivity, but there you had it: one glitch in the schedule and they all flipped.

Deirdre sipped her wine and stepped out onto the front porch. The sun was warm out here still. Two boys shot baskets across the street, both of them in T-shirts and shorts. Deirdre liked picking out the girls in her classes who would wear shorts if they could (not at school, of course) right up until Columbus Day, as if avoiding long pants could keep winter at bay. Fat chance of that happening in New England. In fact, winter came faster each year, it seemed, with intermittent Indian summers, those glorious October days of warm, bright sun and crisp blue skies and even occasionally a warm day or two in November. Still, one or two girls would refuse to wear socks right up until the first snow; their way, Deirdre supposed, of hanging onto the feel of summer. And pushing the dress code a bit too.

A horn honked, and Deirdre looked to see her neighbor Susan parallel parking by the curb in front of her house. She backed in the end of her black Saab and turned off the car.

“Hi there,” Susan called over, stepping from her car.

Deirdre waved, too late to duck into the house and pretend she hadn’t seen her.

“Let me put this stuff in the house and I’ll be right there. I want to talk to you about something.”

Deirdre nodded. “Okay.” She wished suddenly that she hadn’t encouraged Susan to join the board at Brandywine. She looked at the other houses on the street. Three of the four had some relationship to Brandywine, either a current child attended, or a past child, or the parents had some other connection.

Susan walked over holding a glass of white wine. “Thought I’d join you,” she said. “How are you?”

“Okay. I mean . . .” Deirdre shrugged, aware that the wine was making her light-headed.

“So, we had an emergency board meeting this afternoon.” Susan sipped her wine. “I’m sorry.”

Deirdre felt her face growing hot. A board meeting already? She looked to see how Susan was reacting but she couldn’t get a sense.

“I guess Martin thought it necessary to hire a new person right away.” Susan looked away as she said this, over toward the park.

“For how long, did he say? I’m only on leave.” Deirdre tried to keep her voice even, not panicked.

“Martin didn’t want to leave your classes in the hands of a sub.” Susan sipped more wine.

“Who’d he hire?”

“A Mrs. Delambre? Actually, Madame Delambre is what he said.” Susan raised her eyebrows and brought a hand to her heart. “Do you know her?”

“She’s legendary! She taught for years at St. Michael’s. She wrote one of the books we use, the beginning one. Great, this is all I need. Madame Delambre teaching my kids.” All Deirdre needed was for the legendary Madame Delambre to say something to Martin Loring about how her students were far behind where they should be and how their teacher obviously hadn’t taught them much of anything. Plus, wouldn’t Madame Delambre have to know why she had been hired? Even if Martin didn’t tell her outright, by now she would know the reason for Deirdre’s absence—and that meant everyone at St. Michael’s would now know too.

Susan looked right at Deirdre. “Frances Worthington is one powerful lady.”

“Don’t I know it.” She didn’t know how much to confide in Susan about Frances or Anna. “You said you wanted to talk about something?”

“I just wanted to see how you were doing. I imagine this has been a tough day for you.”

“Martin, he’s a good man. He’s fair.” Deirdre crossed her arms.

“Let’s just say that Frances Worthington has a single-minded pursuit right now.”

“But why can’t Martin see this for what it is?” Deirdre blurted out. “Why can’t he see that Frances Worthington is nothing more than a power-hungry woman? She’s been out to get me ever since Anna started the upper school. She hates that I’m gay, and what’s worse, I think Anna’s gay and Frances is taking that out on me. God forbid Frances Worthington might have a gay daughter.” Instantly, Deirdre regretted saying as much as she had. She had no idea really what Susan’s relationship was like with either Frances or Martin Loring. Well, too late.

“Have you spoken with a lawyer?”

“A lawyer? God no! That’s—Martin wouldn’t take it that far . . . He . . . for God’s sake, he told me this morning that we’d work it out.”

“He may have no choice,” Susan frowned. “If I were you, I’d find a good lawyer. Murray and I have one if you’d like. He’s pricey but he’s good.”

Deirdre couldn’t believe what she was hearing. Things were already getting out of hand. “When Martin investigates—and he promised me he would—he’ll find out that there is nothing going on here. I know he’ll do the right thing.”

“He will—but will Frances Worthington? She’s the one you need to worry about.”

“I don’t think Anna will let it get that far.” Deirdre finished her wine. “Sure, I know that Frances has a lot of power—over Anna too—but you make it sound like there’s a lynch mob out there.”

Susan didn’t say anything.

“Was the meeting that bad?”

“It was pretty bad,” Susan said after a moment. She swirled the last bit of wine in her glass. “Ugly. The real problem is that Leo Rivera is still very much on everyone’s mind. Now that they’ve arrested that guy—who, by the way, Murray swears was one of your movers?”

“Oh God, people don’t think he’s some friend of ours or something, do they?”

“No, no.” Susan waved her hand. “But you know, the boy was sexually molested before he was killed and . . .”

Where is she going with this? “And what?” Deirdre put her hands on her hips.

“Well, people—and I’m sure you can understand—get nervous when something like this happens—”

“Of course they get nervous! A little boy is murdered by his next-door neighbor and gets dumped in the river! Who wouldn’t get nervous?”

“But he was raped. And so people . . . feel that . . . having homosexuals around children is too risky. You can see how people might think that.”

Deirdre was stunned into silence. “So what you’re saying is that because Leo Rivera was raped by some crazy man, I might not get my job back?” Her breathing quickened and she could feel her heart racing.

“You’ve got to understand—”

“God, this is crazy. This is too crazy.” Deirdre ran her fingers through her hair.

“I’m just afraid—and I’m sorry to say this,” Susan spoke softly and put a hand on Deirdre’s shoulder, “that Martin Loring will be under a lot of pressure to let you go.” She gave Deirdre’s shoulder a little squeeze.

“Because he’s already under a lot of pressure, you mean,” Deirdre said quietly, tears brimming.

“I’m sorry.” Susan removed her hand. “Any other time, you could explain your side of things. But the way people feel right now, I’m not sure it matters.”

“Guilty before proven innocent. This is just . . . awful.”

Susan took a couple of steps down from the porch. “Remember, the lawyer. If you want his number, give us a call.”

Deirdre watched Susan walk back to her house. What was she supposed to do now? She wondered about Beth Ann. If people were as riled up as Susan suggested, Beth Ann would surely have a hard time defending her, particularly in pu

blic—which is where, it was beginning to seem, Deirdre was going to need some serious defending.

Chapter Fourteen

At four, SJ left the library and drove to First National Bank. She needed to transfer money from savings to checking and drop off the deposit check to the realtor. But Deirdre had whipped up some kind of special dinner—God knows what she was thinking—and either SJ had to tell her about the new apartment or she had to go through the motions of dinner. She didn’t relish either option.

What else to do except play it by ear? If it seemed reasonable, then SJ would bring up the new apartment and suggest, maybe, the idea of a separation. The problem was, of course, when was it ever reasonable to talk about separating? And what kind of person would break up with her girlfriend on the same day that the girlfriend was let go from her job? For that matter, what kind of person would go through all the work of buying and moving into a new house and then leave less than a month later? SJ knew people did such things all the time, you heard about them from friends, you read about them in Redbook and Ladies’ Home Journal in the dentist’s waiting room. It’s just that SJ didn’t see herself as one of those people. When she heard the stories, it was always a man who left an unsuspecting wife, a man you could get angry with for being so insensitive, so selfish that he would leave the relationship that quickly and, the articles always suggested, with so little thought and consideration for the other person. Now, SJ wanted to reread the stories, knowing there was a much bigger part they were probably leaving out.

But she didn’t know how much longer she could continue to live with Deirdre and pretend things were fine.

Not that she was doing such a good job of pretending. This past weekend, SJ hadn’t been around much, and then when she was, things had been tense. She knew that tonight’s dinner would be Deirdre’s peace offering. Deirdre would have spent hours making some kind of fancy dish—or several, and they all would be delicious—and Deirdre would try to apologize for something she wasn’t even sure she’d done. This last part infuriated SJ. Why, instead of trying to get back into SJ’s good graces, couldn’t Deirdre confront her about what was going on? SJ admitted that, a few times over the years, she had deliberately provoked Deirdre to make her angry, to just get her to react, but each time Deirdre responded with puzzlement, first about where the argument had come from, followed by immediately acquiescing, admitting that if SJ were mad, then she, Deirdre, must have done something to provoke her. Each apology came with a lovely dinner. The tendency was to smooth things over and not to deal with them. Of course, tonight’s situation was much worse. The stakes were higher, for one thing. Now, SJ wasn’t simply provoking Deirdre. Now, SJ really wanted out, and her timing was absolutely lousy.

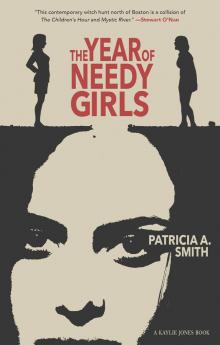

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls