- Home

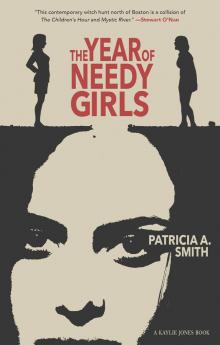

- Patricia A. Smith

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Prologue: August

Part One: September

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Two: October

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Three: November

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Acknowledgments

About Patricia A. Smith

Copyright & Credits

About Kaylie Jones Books

About Akashic Books

To all my students

prologue

august

The air, electric, buzzes and hums. It’s the end of August. One of those humid, still Saturdays, the city empty, or holding its breath.

East of the river, near the abandoned textile mill and the old shoe warehouse, Leo Rivera rides his bicycle, a ten-speed hand-me-down from his brothers. He pays no mind to the heat. Leo stands and pumps past a vacant lot, one of several in his neighborhood, littered with broken glass that sparkles in the sun. Tufts of stiff, burnt grass poke though cracks in the concrete, and red plastic milk crates sit overturned and empty in the lot, waiting for the men who will gather there later to drink beer and listen to the game. Through the opened window of a shingled brown triple-decker, he hears Portuguese, the same radio station his mother listens to, the same one that will broadcast the soccer match this afternoon, Brazil versus Chile.

Leo likes soccer but unlike his brothers, he prefers baseball. Best of all, he likes riding his bike. He pedals hard past the chain-link fence of his school, Most Precious Blood Elementary—MPB they all call it—and the hot tarred blacktop where he will be having recess again in a few short days. He whizzes past Most Precious Blood Church and the white sign that advertises Wednesday-night Bingo in the parish hall next door. His grandmother is a regular. She wins, but not big, not enough to buy him a new bike, which he wants more than anything, which he covets. He doesn’t covet anyone else’s bike, just a Trek he has seen advertised in a magazine, but he knows that wanting things and praying for them is bad. Greed, the MPB Sisters say, is a sin. Not a mortal one, like killing, but a venial one, a misdemeanor. Leo tries to avoid wanting the bike outright because he doesn’t like to disappoint the Sisters at MPB, but worst of all, he doesn’t like disappointing his mother.

His mother tells him that he is her pride and joy. The One Born in America. Does he know how lucky he is to be living in a country where his father can get decent work and he and his brothers can go to good schools? He must thank God for America, his mother tells him. Every night. He must pray and thank God for sending them all to this good country.

The American boy doesn’t know any other country. He hears the stories and he thinks he is the luckiest of all not to know anything but America, this city, this neighborhood where he goes to school and plays baseball, this land of shiny bicycles. At night, when he is saying his prayers, always thanking God for America, Leo slips and tries to make deals about how he will help his mother and how he will do all his homework if he can only get that Trek for his birthday. His birthday isn’t for weeks, but he is thinking about it now, riding past the library, past the empty Little League field with the backstop halfway torn down, past the mechanic shop where Mickey, his next-door neighbor, works part-time. Mickey is almost a friend. He’s much older, but he helps Leo with his bike, lubes the chain for him or replaces it outright like he did at the beginning of summer. Leo is thinking of his birthday and how much he would like that Trek to ride to school and show his friends. He won’t even mind the helmet his mother makes him wear. He won’t complain ever about the helmet, he promises God.

So when Leo coasts down the sidewalk toward his grandmother’s house, a white triple-decker surrounded by a chain-link fence, and Mickey is waiting, sitting in the passenger seat of a car alongside the curb, engine still running, Leo is only thinking of his Trek, seeing himself on the first day of school, riding to MPB on the shiny bike. He isn’t thinking how strange it is that Mickey is here waiting for him. No, he is thinking only of his birthday and the way it will be when his mother leads him to the dining room.

Mickey calls, “Leo!” out the car window and tells him to hop in. In the driver’s seat, a man Leo doesn’t recognize flicks his cigarette butt onto the sidewalk, where it lands next to Leo’s sneaker. Mickey says he’s found the bike. He will buy it if it’s the one Leo wants. Mickey can’t remember if it’s a Trek or not—he thinks it is. It’ll just take a second—he’s seen the bike in a shop downtown and it isn’t too expensive. If they go right now, if Leo will just get in the car and . . . it’ll just take a minute, his grandmother won’t even know he’s gone—she doesn’t even know he’s here yet—then Mickey’ll know whether or not it’s the bike to buy for Leo’s birthday. They’ll bring him right back, they promise.

So his grandmother won’t worry, they put his Schwinn in the trunk. “If she sees the bike lying in the yard, we don’t want her wondering where you are, do we?” Mickey says.

Leo agrees and climbs in the backseat.

Mickey’s friend, the driver, smiles in the rearview mirror. “You like bikes, huh?”

This is too good to be true. This is maybe some crazy dream.

part one

september

Chapter One

At seven thirty, with SJ still asleep, Deirdre Murphy left the house for school. She walked side streets shaded by trees in their glory—pale autumn reds, yellows the color of honey. She scuffed through piles of leaves, each whoosh a reminder of every other autumn and every other beginning of the school year, the only way Deirdre knew how to mark time. She kept track of events based on the girls she taught: the drama queens, the freaks, the year they all were brilliant. This year, Deirdre could already tell after a week of classes, was the year of needy girls.

Each house that Deirdre passed, she tried on. These were not houses meant for her, with their mansard roofs, turrets, and gables. They were dream houses only, forever inaccessible. Still, she pictured herself making coffee in that one. Eating breakfast on the porch of this one. Working in the garden, pulling weeds after school. She imagined herself alone in the houses, NPR on the radio while she cooked dinners with ingredients she grew herself. In Deirdre’s mind, the interiors of the houses were tidy and looked like the magazine pictures she flipped through in the grocery store check-out line. Artfully draped afghans. Throw pillows just so. Old books piled alongside the fireplace—dust free, all of it. The pictures, so sharp and real they made her ache with longing, became fuzzy if she tried to include SJ. Then the images slipped away and she was back on the outside looking in.

Seventy September degrees. Blue, blue sky. Who could tell that just days before, Hurricane Rita had blown through, canceling school? Or that over in the East End, the Rivera family was mourning their missing child? Outside, the city was moving. Men and women, courier bags slung over their shoulders, hurried toward the train station to ca

tch the commuter rail into Boston. Deirdre could tell if she was running late by the location where she crossed paths with the woman from Hanley’s Hardware Store, where she and SJ had just bought their first power drill. Every day this past week, the woman, stout and square with a kerchief tied over her stiff, beauty-parlor hairdo, smiled and waved good morning to Deirdre. A steady stream of familiar cars crawled by on the street, the carpool brigade on its way to Brandywine Academy.

An institution in town, Brandywine was in many ways a typical private school—small with a kind of clubby feel about it, catering to the more prominent families in Bradley, Massachusetts—with girls whose last names were Saltonstall, Hallowell, Conant, Fitzgerald. Except for the fact that it was surrounded by blacktop and a parking lot, Brandywine could be mistaken for another of the larger houses in the neighborhood. But there it was, next door to the Blue Moon Café, the favorite hangout of Brandywine parents, the ones who didn’t work or who drove the carpools in the mornings and afternoons. On the front door of the Blue Moon, Leo Rivera’s face fluttered from a flier with taped corners. Smiling, in that blue Red Sox cap. Deirdre pushed the door open, breathing in freshly ground coffee, rich, buttery croissants.

Frances Worthington and Evelyn Moore, the mothers of Deirdre’s two neediest sophomores, sat huddled at a table off to the side and toward the rear. Frances, with her back to Deirdre, seemed to be doing the talking. Elbows bent at her sides, she twirled manicured hands in the air. Frances was the president of the board at Brandywine and her husband, a child psychologist, enjoyed a successful private practice. He was pretty famous and appeared from time to time on morning talk shows. Around town, word was that he was having an affair—the former babysitter, a girl closer in age to his own daughter—but the talk shows never mentioned that.

Evelyn sat across from Frances, nodding. Her small round face bobbed to the rhythm of Frances’s hand motions. Evelyn glanced briefly up toward the door, but Deirdre looked away in time, fumbled in her backpack for the money she already gripped in her other fist.

“May I help you?”

“Um, yes, a decaf latte,” Deirdre said. “Skim.” She felt her face grow hot as if the counter girl knew what Deirdre was doing, as if she had been caught in a lie. The girl didn’t show any emotion even though Deirdre was one of her regular customers, coming in most days before school.

Deirdre moved away from the register to wait for her latte. She looked around at the art hanging on the walls, art that changed with some regularity, most of it modern and urgent-looking, as if the artists heaved it onto the canvases in one violent push. Some of the paintings still looked wet.

“Yoo hoo! Deirdre?” Evelyn Moore half-stood, hovering over her chair, waving with her fingertips.

Hi, Deirdre mouthed, and waved back.

Frances turned and looked over her shoulder, smiled a gracious lipstick smile, the kind she learned how to do as president of the board, the kind the counter help would never attempt. “Deirdre.” That smile again. “How nice to see you,” Frances said.

Nice. Deirdre glanced at her watch and frowned, the comic strip balloon above her head saying, Oh, look how late it is. I’ve got to go.

Evelyn said, “I was hoping I might run into you this morning.”

Uh-oh. That meant kid trouble. “Is everything okay with Lydia?” Deirdre crossed the café to their table.

Evelyn brushed her frosted hair behind her ears and tugged her cheery blue sweater over the tops of her corduroys. “I bet you didn’t know you were the topic of conversation at our dinner table,” Evelyn said. “Ev-ery night.” Evelyn took a sip of her coffee and smiled, lipstick-less, at Deirdre. “You are a big hit.”

Frances tapped her manicured nails on the café table, wrapped her other fingers around her coffee cup.

“Oh, thanks,” Deirdre said. “I guess.” She laughed, glancing first at Evelyn and then at Frances. Frances said nothing, shrugged her eyebrows, and took another sip of coffee.

“It’s true,” Evelyn said, motioning to Frances. “Tell her. Anna’s the same way,” she said.

Frances blushed, ever so slightly. Her lips parted and she frowned. Turning back to Deirdre, she said, “The girls do like you. There’s no doubt about that.”

“Well, that’s nice to hear,” Deirdre said, picking up her latte and readjusting her backpack.

“Finally,” Evelyn said, “a teacher who understands our girls. I think it’s great.”

Deirdre took a step away from the table.

“Oh, and Lydia can’t wait for Friday,” Evelyn said, talking with her hands. “She is so impressed with the way you insist they learn about Africa. French isn’t just spoken in France, Mother, she says to me. It’s spoken in West Africa and Canada and even Vietnam.”

At that, Frances rolled her eyes. “Vietnam, honestly,” she said. “The next thing, you’ll be wanting to take our girls there.”

Deirdre laughed. “Oh no,” she said. “I can’t imagine that.” She looked at her watch. “I should be going. Lots to do before school starts.”

Outside, Deirdre squinted in the sunshine. Brandywine’s parking lot was nearly full, and the long line of cars inched their way down the street to the drop-off area. The girls gathered in groups on the blacktop. They wore new outfits, carried shiny backpacks and lunch boxes. It was a scene replicated in schoolyards everywhere, even across town at Most Precious Blood Elementary. But this year amidst all the newness, the haircuts and outfits, the resolutions of a few seniors to make something of this year; amidst the freshmen who were officially high schoolers and important members of the upper school; amidst the braces and eye shadow, the ear piercings and growth spurts; and even down amidst the littlest ones with shiny Mary Janes and hopeful expectations about their new teachers, there were reminders that this year, things were different. Because a child was missing. And though Leo Rivera was not one of theirs, he was still part of the community.

* * *

Deirdre’s classroom was covered with photographs she had taken during all her trips to Paris and the south of France, trips that usually included students. Each time she went, she collected more things—train schedules, pages from hotel phone books, menus, copies of her own restaurant bills, maps of Paris—she saved everything. These objects made the language come alive for her students in a way no textbook could. When her students practiced ordering food, they used real menus. When they learned to tell time, they asked questions with train schedules. Deirdre had a prop for any kind of dramatic situation. She was intent on bringing the real world into her classroom.

This morning, Deirdre had to finalize the plans for her Friday field trip to an African art gallery, a new one, just opened in the East End. She’d had to fight for this trip. Since Leo Rivera’s disappearance, parents weren’t excited to let their daughters venture to the East End, even for a supervised class field trip. The exhibit at the gallery featured the Dogon, a region and people in Mali, known especially for their intricately carved wooden doors. The Dogon were cliff dwellers, still even today, and Deirdre wanted to show her students firsthand examples of their impressive artwork. She’d had to convince Martin Loring that the kids would be strictly supervised and she’d had to convince the girls that nothing awful would happen to them.

Deirdre dumped her backpack and headed to the office to pick up her signed field trip forms.

“Morning, Lil.”

Lil worked in the front office. Had been there since the day the school opened. Technically, she was an administrative assistant, but that title didn’t do her justice. Lil ran the school. When teachers needed something, they came to Lil. When parents had requests, they called Lil. Martin Loring was the headmaster, but Lil did all the work.

“Lil, I’m looking for those field trip forms? The ones for Friday?”

The phone rang. Lil held up her index finger. “Brandywine Academy,” she sang into the phone. On those rare days when Lil was sick, the school didn’t run as smoothly. Audiovisual requests went unfilled. Ca

rpool notices didn’t make it into the right hands. And Martin Loring went into overdrive, overcompensating for being without Lil to tell him what to do. Now that she was nearing sixty, everyone was afraid that Lil might retire soon, and Brandywine without her didn’t seem possible. It remained an unspoken fear that when Lil went, Brandywine would close down.

“Hey,” Forest Macomber strolled in, carrying a pile of books over to the photocopy machine. He looked over his shoulder. “Weird they found that kid, huh?”

“What?” Deirdre turned to Lil and mouthed, I’ll be right back. She followed Forest into the faculty workroom. “When?”

Forest fanned open a copy of Best American Short Stories facedown on the machine. “Jeez, where’ve you been? It was all over the news last night. And this morning.”

“Where’d they find him?”

Forest punched in the number of copies. A piece of paper emerged looking like a crumpled fan. “Shit. This thing jams every time I need it.” He stopped his copies and opened the front of the machine.

“It’s bad, isn’t it?” Deirdre shifted her weight.

“Yep,” he said. “It’s bad. Found him at the bottom of the river, in a plastic container.”

“Oh God.” Deirdre hoped her students hadn’t heard yet. They would want to talk about it. All week, every day since school started, somebody brought up Leo Rivera. The newspapers covered it daily on the front page and then in the City section, a kind of lurid human interest story, like a bad soap opera. Each night on the news, there was Leo Rivera’s face, a sweet smiling boy in his baseball cap.

Forest pressed the red lever, lifted the top of the photocopying machine, and pulled out the piece of stuck paper. He crumpled it up and threw it in the trash. “I need these first period,” he said and looked at the clock. “Shit.” He slammed the top down and looked at Deirdre. “I guess he’d been dead awhile,” Forest continued. He turned back to the machine and started copying again. “That poor mother. She looked awful.”

“Well, can you even imagine? Your ten-year-old kid disappears like that without a trace, and they find him in the river! In a container!”

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls