- Home

- Patricia A. Smith

The Year of Needy Girls Page 2

The Year of Needy Girls Read online

Page 2

Forest gathered his collated copies and switched books. He shook his head. “Makes you wonder.”

The bell rang and there it was, the chaos of the day erupting. Shrill girl voices and high-pitched squeals. Little bodies running pell-mell toward the first and second grade classrooms.

Forest swore again. “Listen, Deird,” he said. Only Forest and her brother Paul could get away with calling her that. “Would you mind . . . ?”

Deirdre waved him away. “Don’t worry about it,” she said. “I’ll keep an eye on the lovelies.” With that, she turned and walked back through the office. Little kids crowded around Lil’s desk, their pudgy hands holding out crumpled envelopes with money for the Fall Supper or raffle tickets or maybe even tuition payments. It was amazing what parents entrusted their children with. Deirdre tousled the hair on one little girl. Savannah, she thought her name was.

“Hey,” the girl said and turned, grinning a toothless grin, cheeks dotted with brownish freckles. Deirdre smiled back.

The others clamored and waved their envelopes at Lil. “Hold, please!” she said into the telephone. “Deirdre?” Lil flashed a stack of papers held together with a paper clip.

Deirdre reached over the little-kid heads and took her field trip forms. She climbed the stairs and thought about Leo Rivera’s mother. How do you survive something like that?

* * *

In Deirdre’s room, the students unloaded backpacks into their lockers.

“Morning, everyone,” she said and walked to unlock and open the door between her room and Forest’s. The girls stood huddled around Morgan Abernathy, one of the most popular tenth-graders.

“Hey, girls!” Deirdre yelled over to them from the doorway. “Mr. Macomber is on his way up, okay? Behave yourselves.”

The little group broke apart and eight or nine faces turned to look at Deirdre. Morgan emerged from the center. “Did you hear about the Rivera kid?” she asked, walking in long, even strides. Her jeans sat just below her hips, belted. “How they found him?” Morgan’s blond hair was cut short, a Charlize Theron look-alike.

“Yes,” Deirdre said, taking a deep breath. “I did.”

“What?” Lydia Moore walked up behind Deirdre.

“Saw your mom this morning,” Deirdre said, turning to Lydia. “In the Blue Moon.”

Lydia rolled her eyes and draped herself over Deirdre’s shoulder.

“Don’t be such a lezzie, Moore-head.” Morgan rolled her eyes and crossed her arms.

“What?” Deirdre said. “Morgan, what did you say?”

“Sorry. But I mean—” she gestured to Lydia, who hadn’t moved, “it’s gross.”

Deirdre shook Lydia off her shoulders.

“It isn’t gross,” Lydia responded, rolling her eyes.

“Whatever.” Morgan sauntered back across the room. Her long-sleeved T-shirt just reached the top of her jeans and she left behind the clean smell of Tide laundry detergent and a sweet, sharp perfume.

Lydia leaned in closer to Deirdre. “My mother says her mother is a real jerk.”

“Lydia!” Deirdre frowned. She should have said something to Morgan. She’d had the perfect teachable moment and she’d let it pass. The girls in Deirdre’s homeroom sat grouped on top of the desks or leaning against the lockers. Deirdre glanced around. “Where’s Anna?”

“Field hockey meeting. Remember?”

Deirdre didn’t but said she did. She watched Lydia skip over to one of the groups and slide up on a desk next to Hilary, lean in, and rest her head on Hilary’s shoulder. They were beautiful girls. Lydia, with that long, shiny hair and brown eyes. And Hilary. She had an athlete’s body, an effortless beauty. Natural blond curls framed her face. Clear, creamy skin. Even in the dead of winter, Hilary liked to wear sleeveless sweaters. Deirdre had joked with Forest once that it ought to be against the dress code, girls with arms like that wearing sleeveless tops.

Forest, out of breath, cut through Deirdre’s room to his, arms full of books and photocopies. “Hey, thanks. I owe you one.”

“Yeah, right,” Deirdre said. The girls were used to Forest’s scatterbrained ways. They adored him. He always managed to train one of his homeroom girls to take attendance.

Deirdre shut the door between the two rooms and turned back to her own class. She watched the girls laugh, talk about their TV shows, their homework. They seemed so comfortable with each other, so at ease in their own bodies, definitely not the way Deirdre felt about herself back when she was fourteen and fifteen. Even now, the girls had a way of making Deirdre feel self-conscious. They had a sense of how to wear their clothes that Deirdre was convinced came only with a private school education. Her students, all of them, had a kind of clear-skinned, Breck Girl confidence that she had always lacked. And no matter how hard they tried, to Deirdre, they still looked like rich kids.

This trip to the gallery would be an eye-opener for them, she thought with satisfaction. Deirdre unclipped the field trip forms and flipped through them. Seventeen, eighteen, nineteen. She counted again. Nineteen. Which one was missing? She put each form on her desk and read the names. Hilary. Lydia. Even Morgan. She looked again. They were all there, all her tenth-graders, except for Anna. Left stuck on the last form, a yellow Post-it with Martin Loring’s handwriting, doodles from a phone conversation—D. Murphy circled in black pen.

THE girls

The girls acted as if they themselves had known the murdered boy, had babysat for him, though of course none of them had. None of them would have ventured into Leo Rivera’s neighborhood; their mothers wouldn’t have allowed it, wouldn’t have wanted their daughters parking the BMW on the street. The Volvo might have been okay, especially an older model—it wasn’t the type anyone wanted to steal, not in that neighborhood—but the girls would still have had to walk alone on darkened streets. For all the mothers knew, their daughters might be alone in houses without security systems, houses that, according to the nightly news, got broken into with some regularity. No, it was certain that none of the girls had babysat for Leo Rivera.

They might have babysat for boys who looked like him, ten-year-olds with gangly arms, scarred knees, and sharp elbows. After the news of Leo’s murder broke, the girls might have inexplicably teared up the first time they babysat their charges, unconsciously making the connection between the dead boy and this living one, a boy they had previously felt neutral toward but now they couldn’t help but hold and kiss on the top of his sweaty head because all they could see when they looked at him was Leo Rivera, his body buried in a container of lime, skin dissolved like an animal carcass.

The girls think of the boys they know—their brothers, boys in the neighborhood, the ones they babysit—as vulnerable. The way the boys scratch at their mosquito bites and pick at their scabs. The way their pants hang when they don’t wear a belt, laces straggling from worn-out sneakers. Even the way the boys swagger onto the baseball field and nonchalantly toss gloves onto the bench makes the girls catch their breath and wonder at the flutter they feel in their chests. They wouldn’t know how to name what they’re feeling, wouldn’t yet understand that now, every boy in town is a stand-in for Leo Rivera. The girls might even worry that what they are feeling isn’t normal, some mixture of maternal, big-sisterly affection and longing, some weird form of desire to which, if they were Catholic, they would have to confess.

Except they wouldn’t. Even in Confession, the Catholic girls can’t admit that what they feel for someone else’s brother might be—they can’t even whisper it, can’t let their minds think it—might be sexual, might have the least bit of connection to that pervert, that monster who molested and then killed Leo Rivera.

Anna Worthington’s mother refused to discuss it. When Sam started wetting the bed, an old problem their mother thought they had conquered, only Anna thought there might be a good reason. Anna could point out that Leo and Sam were on the same Little League team, the Wildcats, and that it was only normal for Sam to wonder if what had happened to Leo coul

d happen to him too. If their mother would only talk to other Wildcats moms, she might find out that their sons had also revived or, in some cases, started questionable behaviors—another couple of bed-wetters and one boy, Eli, a friend of Sam’s, had even gone back to needing a nightlight.

Chapter Two

SJ pulled up to the intersection in front of the library. A police cruiser, blue light spinning, idled at the curb. SJ had received two tickets for sneaking through yellow lights at this very intersection. She flicked on her left blinker, glanced over at the guilty driver—a black kid (no one she knew)—and took a left-hand turn into the employee parking lot.

“Thank God, thank God!” Like an apparition, Florence emerged from the tall green bushes that lined the perimeter of the stone-faced library and hurried toward SJ’s car. Florence waddled a little, like a penguin, in her pumps.

“Florence, were you hiding?” SJ laughed, then rolled up her window. She got out of the car and pulled her tote bag from the backseat of the Honda. “What’s going on? What are you doing?”

Florence seemed startled. She clutched the brooch at the nape of her neck. Another scrimshaw. For all of SJ’s seven years at the library, Florence had been writing a book about the wives of whaling captains. Even during SJ’s job interview, Florence had sneaked in several references to her whaling obsession. How, SJ couldn’t remember anymore. But half-kidding, SJ had said then, “Maybe in a previous life, you were the wife of a whaling captain. Or the captain, even.” Florence had seemed to like that. She had offered the job to SJ on the spot.

“You’ve heard, haven’t you?” Florence said now to SJ in the library parking lot, the sun directly overhead and Indian-summer warm.

SJ locked her car. “What?” she asked.

“They found the Rivera boy.”

SJ stuffed her keys into the pocket of her black jeans.

“They found him . . .” Florence fiddled with her scrimshaw.

“Dead?” By this time—two full weeks after he’d disappeared—no one really expected to find the boy alive. Of course he was dead. But you still hoped.

Florence held up her hand. “They found him in the river. You didn’t hear? It was all they talked about on the news last night. And this morning. It’s more horrible than horrible . . .”

“Oh God.”

“Yes, terrible.” Florence stopped walking. “SJ, the police have been around, asking questions.” She slid her brooch back and forth along its pin. She folded her arms.

“And . . . they think, what, that we have a clue? Do we have a clue?” SJ put down her tote bag and stood facing Florence. Leo Rivera was a neighborhood kid. He came into the library from time to time. Yes, SJ had seen Leo in the library before, but she didn’t know him, not the way she knew some of the other kids, the regulars. She didn’t remember the last time she had seen him—probably sometime over the summer, before school started back up again. SJ had told all this to the police officers who’d come around immediately after the boy disappeared.

“SJ, listen. That guy, Mickey . . . ?”

“My student Mickey?”

“Him, yes. I think he might be involved.”

“What?” Ever since SJ had suggested to Florence that she might have been a whaling captain in another life—that she might have had another life—Florence swore she had psychic abilities, that she knew things.

Florence shook her head. “Sara Jane, listen to me. I don’t know. They had questions about him. Who he was, what he did here at the library. I said you knew him, not me. They came in again this morning, when the library opened. I told them you didn’t come in until the afternoon.”

SJ shielded the sun from her eyes.

“I told them he’d be in later today and they seemed to like that. Now, if there’s something to this, we might be in a whole lot of trouble, letting him hang around the library like we’ve been doing.”

“Hang around? He’s learning to read, for God’s sake. Isn’t that what we do here in the library? Help people to read?”

Kids in this neighborhood got no breaks. You always heard on TV about things going on in the East End—break-ins, shootings. (“Jeez, SJ,” Deirdre would say, “we need to find you a new job.”) SJ looked at Florence here in the sunlight, a short, middle-aged white woman whose colored hair was professionally styled at least every three weeks, whose husband retired early from a banking career. Florence, in her Evan Picone suits and crisp Talbots dresses. Her scrimshaws and pumps.

But this was Florence. Her friend. Still, sometimes SJ didn’t think that Florence had a clue about the real world. Florence ran the library. Had been its director for over seventeen years now. She hadn’t left when things got rougher in this part of town. She never requested a transfer. Florence began beeping her car secure—something that SJ found ridiculous and somehow offensive—but Florence didn’t quit her job. She kept working at this library in this bad part of town. Why couldn’t SJ admit that maybe Florence knew more than she gave her credit for? Why couldn’t SJ consider that Florence might have some words of wisdom about things other than relationships? Or that maybe Florence cared about this neighborhood as much as SJ did?

“So, what do we do?” SJ looked at the ground, pushed gravel around with her foot. “Should I cancel his tutoring sessions? What?”

“Listen to me.” Florence took hold of SJ’s shoulders. “If those detectives come in looking for him, we will let them. If he . . . that man . . . Mickey . . . is involved in this terrible, terrible murder, we will want him to be caught. Won’t we?”

SJ looked at Florence. Those eyes, warm pools of blue-gray, soft and deep. Florence seemed to be reading SJ’s face, looking for a way in, a way to make her understand. She gave SJ a little squeeze and removed her hands. In the distance, a siren wailed.

“Let’s go,” Florence said.

Mickey. Involved in a murder. Do child killers want to learn to read? Do they look awestruck when they manage whole sentences on their own?

“This is crazy.” SJ lifted her tote bag onto her shoulder and climbed the steps. At the top, she opened the door and paused, turned back around to Florence. “Does he seem like a killer to you?” She wanted to say, Do I look like someone who would mistake a murderer for a nice person?

Florence shrugged. “Come on, SJ. Let’s go inside. You’re already late.”

* * *

When Mickey Gilberto had first sauntered into the library the day after Labor Day in a blue mechanic’s uniform, SJ recognized him immediately.

“I know you,” she had said. “You moved us in.”

Mickey looked blank.

“The green house? Lime green, over on the west side?”

“Oh yeah,” he smiled. “That house. Christ, I never seen a house that color before.” He laughed. SJ couldn’t tell whether or not he was making fun. “It’s a great place, though . . . inside,” Mickey added. “You own it, right?”

“Yes,” SJ said. “We own it.”

“You and the other girl . . . you own it together?”

This was one of those questions that took SJ by surprise and that she didn’t know how to handle. It struck her as a personal question, crossing some invisible boundary or at least teetering over one. She found herself blushing. “Yes,” she said, “we own it together.”

“So, you’re a couple?”

And now, the result of having answered the first personal question, SJ was in an awkward position. Now SJ was in a place she didn’t want to be. Not that her relationship with Deirdre was secret, definitely not. The question wasn’t phrased with any particular tone, no edge that SJ could discern, but what was he after? Was he making conversation, or was he fishing? The question—you’re a couple?—made SJ a little suspicious, unsure of his motives. She didn’t know how to answer. She didn’t want to seem embarrassed or secretive but you had to be careful. You had to at least wonder if this guy was a nut case.

“Hey,” Mickey said, taking a couple of steps back from the front desk, hands up, �

�whatever. That’s cool if you are, cool if you aren’t. Whatever floats your boat, you know what I’m saying? I got nothing against gays.”

SJ fiddled with the pencils in the holder on the front desk and tried not to seem flustered. “I’m afraid I’ve forgotten your name.” She could feel the skin burning on her neck and along her jawbone.

“Mickey,” he said, sticking out his hand. “Mickey Gilberto.”

Now SJ remembered. She recalled the other mover, the older guy, calling out to Mickey on the sidewalk in gruff, accented English. She remembered Deirdre yelling from the bathroom later that night, her mouth full of toothpaste, “Didn’t that Mickey guy weird you out?” and SJ saying truthfully that she hadn’t noticed anything strange about him. Here, with Mickey right in front of her, SJ decided that Deirdre had disliked him because of his bad skin and because he looked poor. SJ couldn’t admit to herself that maybe she had mistrusted Mickey’s motives for the very same reasons. “Yes,” SJ said now, “Mickey, that’s right. I’m SJ.” She shook his hand. “So, you’re a mover and a mechanic?” she asked, pointing to his uniform, Bob’s embroidered in red on his breast pocket.

“Yeah. Extra money, you know—something to keep me out of trouble on weekends.” He grinned.

Mickey had a lazy way of talking and when words came out of his mouth, they sounded droopy and thick. SJ caught herself wondering if he was high but pushed the thought out of her mind. He had a lazy stance too, as if his limbs weren’t quite attached to the rest of his body. At any minute, it seemed to SJ, his legs might buckle beneath him.

Mickey had come to the library, he said, to learn to read. He hadn’t ever learned correctly, he told SJ. Hadn’t ever really bothered. “It wasn’t like I was the best at school, you know what I’m saying?”

SJ could see him: A scrawny kid, with the kind of face that looked like trouble. A wise guy. She imagined him as a prankster maybe, the kind of kid who spent too much time in detention but who wasn’t bad, really. Mischievous. An imp.

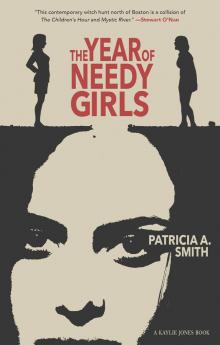

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls