- Home

- Patricia A. Smith

The Year of Needy Girls Page 24

The Year of Needy Girls Read online

Page 24

“Letters to the editor? Yeah. You’ve got to ignore them.”

SJ scoffed. “Sure, that’s easy.” She motioned toward the door. “Deirdre doesn’t know about them yet.”

“Oh boy.” Murray resumed scrubbing. “You girls are in for a rough haul.”

* * *

Inside, Deirdre was collapsed on the couch, newspapers in her fist.

“Oh—I was going . . . I meant to get rid of those.” SJ rushed over and sat next to her.

“God, you knew about these? But you didn’t say anything to me!” Deirdre’s face was tear-streaked.

SJ swallowed. “No. I didn’t know how . . . or if I should. It’s so mean-spirited.” She tried to take the papers away.

Deirdre held on and shook the stack of them. “Frances Worthington—I’m sorry. She is just a horrible person.”

“Agreed. She is, and I know this is easier said than done, but you need to try and ignore these, okay?” SJ reached again for the newspapers.

“Ignore? How can I do that? There’s hate speech scrawled in front of our house. The neighbors are so mortified they try to clean it off—”

“No, Murray just wanted to help! He was trying to get rid of it before you came home!”

“You know my life is ruined! I won’t teach again.” The tears poured forth. “I mean, I’m clear on that now. There will be no teaching for me, not anywhere within a hundred-mile radius of this place—Frances will make sure of that!”

SJ sat, hands useless in her lap. “Did you see the letter I wrote?”

“You did? No, how’d I miss that one?” Deirdre’s eyes lit up a little. SJ pulled out first her letter to the editor and then Beth Ann’s.

“Beth Ann. Wow, what a sweetie.” Deirdre wiped her face.

SJ raised her eyebrows and folded her arms in front of her chest.

“No, no—I mean, your letter is amazing too. It’s just that . . . Beth Ann doesn’t have a reason to write, you know? Not that you have a reason, but I mean, you love me. Beth Ann could just stay out of the whole thing.”

It was this ability of Deirdre’s to ignore what was right in front of her, to go looking for some sort of approval from people she didn’t even know or have reason to care about instead of focusing on the love she did have, that drove SJ crazy. “Right,” she said to Deirdre now. “I love you.” And somehow, she thought, that makes me about as good as chopped liver.

* * *

For the three days she was in jail, Deirdre hadn’t really thought much about Mark and Sophie, about what to tell them, how to make the story sound . . . kid-friendly. But there was nothing about sex that was kid-friendly. She didn’t know what she’d say when the time came. In jail, Deirdre had spent her time thinking about Frances Worthington, about how cruel she was and how much power she had, about Anna and the other girls. Deirdre wondered if all the other girls believed what they had heard. She wondered, too, about Forest. She wondered if the neighbors had decided that she was really a child molester or whether they felt sorry for her. She wondered if she and SJ would make it as a couple, and if they would have to move. She thought about how your life really can change in an instant, as crazy and clichéd as that was, and about how little control anyone had in spite of all the things everyone did in order to pretend they did. All the steps you took in order to ensure your future. If I go to this school, if I get this job, if I live in this neighborhood . . . What a farce.

Now, it was almost Sophie’s birthday, and Deirdre hadn’t heard from Paul since the bond hearing. Normally, she would go and help out with the party, but she didn’t know whether or not she was welcome this year.

“Call Kris.” SJ handed her the portable phone.

Deirdre shook her head. “I don’t know. I don’t think I can.” She swallowed. “Can . . . Could you call?”

“What, and ask if it’s okay for you to come help with the birthday party? C’mon, Deird.”

“I know,” she sighed. “I just don’t want to talk to Kris.”

“You’ll have to face her sometime though, yeah? Why not get it over with? Might be easier on the phone first—that’s what I’d do.”

Deirdre didn’t want to talk to Kris. She didn’t want to talk to anyone. She wanted her life back. She wanted it with an ache so strong it threatened to burst within her. She couldn’t keep it inside. She paced. She flopped. She slept. She zoned out in front of the TV. Nothing helped. She didn’t want to go outside because she didn’t want to see anybody. By now she was certain the entire town knew about her arrest, and she couldn’t face the stares, the looks, the whisperings she was certain would be directed at her. How did Hester Prynne do it? she wondered. How did she face that town with her quiet pride and go on living her life, raising Pearl, not minding what anyone said or did? Deirdre didn’t think she had the strength in her.

* * *

“You can’t stay in here forever,” SJ said the next morning when Deirdre refused to get out of bed. “Why give them,” she motioned to the windows and beyond, “why give them that power over you?”

Deirdre let SJ talk her into a walk through town. They bundled up in turtlenecks and sweatshirts, but Deirdre wished they had grabbed mittens too.

“It’s freezing out,” she said, shoving her hands in her pockets.

Deirdre and SJ walked the streets of their neighborhood. They walked past the graffiti, duller now but still visible. Deirdre tried to avoid looking at it outright but glanced down and saw just enough of the lettering to make her stomach clench. They walked past Susan and Murray’s house. Deirdre didn’t look over. They walked through the park and Deirdre realized it had been a good long while since she had been for a run. She imagined herself out on one of her regular routes—feet hitting the pavement, her legs in long, even strides, feeling strong.

“So, Paul hasn’t even called me yet and he knows I’m home,” Deirdre said.

SJ pulled her sweatshirt sleeves over her hands. “He’s probably not sure what to say, you know?”

Deirdre nodded. “It’s just . . .”

“I know.”

There were still bursts of flaming orange and piercing red on the trees, oaks and a few glorious maples, but more leaves lay scattered on the ground, covering the grass and parts of the walkways. The tremendous beauty of fall was so short-lived.

“You need to call them,” SJ said.

“And why haven’t my parents called? Jeez, you’d think they’d call me.” She kicked at some leaves. And Forest. It had to be all over school that she’d been in jail. “Did . . . did anyone call while I was . . . away?”

SJ looked over to the basketball hoops. “I had a visitor while you were gone.”

Deirdre stopped. “A visitor?”

“Mrs. Gilberto.” SJ swallowed. “Mickey’s mother?”

Deirdre’s heart thudded against her chest and her mouth went dry. She couldn’t even ask a question. They both stopped walking.

“She wanted to know if I could help Mickey.” SJ turned to face Deirdre. “She wants me to visit him, at least. He has no one.” She shrugged.

Deirdre felt an urge to scream. And run. She heard again the detective’s voice: You knew your partner was tutoring Mickey Gilberto? “SJ, some police detectives came by to interview me about Mickey Gilberto.” She waited for a reaction. “I didn’t mention it because . . . well, because then I . . .” She hesitated and took a deep breath. “I went to P-town and then . . . everything happened so I haven’t had a chance.” The truth was, she hadn’t thought about it much since then—at least not until she saw Mickey Gilberto that day in court.

SJ looked flushed. And flustered.

“I went looking for you at the library—did Florence mention it? We chatted for a bit. And I ran into Anna Worthington.” Deirdre took another breath, realizing she was talking quickly, running her words together. “So that’s when I got in the car and drove all the way to the Cape. I don’t know why. Driving calmed me down. I didn’t know what to think,” she said, trying to

make SJ understand that she had been thrown off by the police visit, by not finding SJ at the library. “The cops wanted to know why you were hanging around Most Precious Blood Elementary and I didn’t know what to tell them. I said you were probably at work, taking a break, but then I found out you’d called in sick and, I don’t know, I got worried. I mean, the cops practically suggested you were involved with Mickey Gilberto!”

SJ stood silently, stony faced.

“You’re not though, right?” Deirdre asked quietly.

Leaves whirled around them in the wind.

Before SJ could say anything, Deirdre continued, “I know you were tutoring him. I mean, that’s okay, and I get why you didn’t want to tell me you hadn’t stopped. Though you really could’ve, SJ. I mean, jeez. I just . . . I don’t know . . . I had this awful gut feeling that somehow there was more going on there. I mean, when I mentioned it to Florence and she pointed out how stupid and silly it sounded, I had to agree. But you’d been so strange and I didn’t know what to think . . . Say something!”

SJ turned and started to walk toward the park gate.

“We need to talk about this stuff!”

SJ spun around. “Then what happened in P-town, huh? Tell me about that!”

Deirdre felt the tears building but willed them to stay put. “I know, I know. I need to tell you about that. But for God’s sake, SJ, you rented an apartment!”

SJ stood and planted herself. She faced Deirdre squarely. “I’m here, aren’t I? I didn’t leave.”

“But did you want to? Are you here and you wish you weren’t?” The tears had a life of their own now and Deirdre couldn’t help it. She wiped them away. “Crap, SJ. If you want to be gone . . .” she couldn’t believe she was about to say this,” it’s okay. You should leave. If that’s what you want. Not that I’m not grateful you stayed until now. I couldn’t have made it through this without you.” She dug in her jeans pocket for a Kleenex. “Crap,” she said and looked at SJ, expression hardened, cold and distant. “I’m serious. And . . . I hope you don’t leave. I really want to be with you. But if you’re staying because you feel sorry for me, you should go.” Deirdre said these last words softly, but she felt their trueness. It would be okay. If SJ wanted out, Deirdre could let her go.

part three

november

Chapter One

November loomed outside the window, gray and overcast. This was the depressing part of autumn that even in New England made you think about Paul Verlaine and his long sobs on the violin. SJ almost knew the poem “Autumn Song” by heart; Deirdre taught it to her ninth-graders every year and so ended up reciting it at home. Every year she said, “Did anyone ever really feel like that? How could Verlaine be so pessimistic about fall?” And every year SJ reminded her that Verlaine was clearly talking about November and not September or October.

This year, November stretched particularly long and cold and drab. Not much to look forward to—and SJ hadn’t yet been to visit Mickey as she had promised. She couldn’t put it off any longer, so she pulled on a thick turtleneck sweater and gathered her hair into a ponytail.

“Hey, hon?” she yelled from the bedroom.

No answer.

SJ peered into the dining room. Beyond the archway, in the living room, Deirdre slept curled on the couch. SJ stuck her wallet in her back jeans pocket and grabbed her keys from the top of the bureau. She threw on a down vest and unlocked the front door.

Deirdre rubbed her eyes. “SJ?”

“Be right back. Just got to run this errand.” And SJ slipped out.

* * *

The jail parking lot was almost full. With holidays approaching, visitors became more frequent. SJ stood in line before the metal detector. She put her wallet and the down vest on the conveyor belt.

“Name?” the guard with the clipboard asked her. He searched on the visitors list and checked her off.

“We’re full up right now. Next group,” the guard told her and pointed to an empty hard plastic chair in the hallway, the last one in a row of people. SJ was aware of how few white people there were. She pulled the chair out from the wall.

“Excuse me,” she said to the older African American man in the next chair. He stared straight ahead and said nothing.

SJ hadn’t thought about Mickey much in the last couple weeks, not since Deirdre had been arrested. Promising his mother she would come had been a mistake. It seemed years had passed between September and now. She had been another person then, and today she felt like a newer, smarter version of herself. She wanted to get up and leave, bolt without saying anything. She glanced at the man next to her, noticed his white eyebrows, thick and unruly. He clutched a cap in his hands. She wanted to ask him whom he was here to visit. So many people. Could it be that all of them were visiting someone who had committed a crime? Were there that many criminals?

* * *

Two guards accompanied Mickey and led him to the chair opposite SJ behind the glass. This was a different visiting room than the one where she had met Deirdre. He picked up the phone. “Hey,” he said. He slouched in the chair, all knees and arms and torso, ankles shackled.

“You look tired,” SJ said. The jumpsuit was baggy; his face looked more angular, sharper. She thought about Detective Mahoney’s words, how they had strong evidence against him. “Your mother said you wanted to see me?”

Mickey shifted in his chair. “This hellhole,” he said. He sounded like a little kid, plaintive and suddenly earnest.

“I’m . . . I don’t think we’re supposed to discuss anything.”

Mickey leaned forward, his jaw tensed. “You gotta help me.”

A guard peered over from across the room.

“Mickey . . .” She couldn’t bring herself to ask the question, half afraid of the answer, half certain suddenly that she already knew, certain in any case that they couldn’t discuss it here. She just looked at him. What could she say?

Mickey’s eyes clouded over, and for a second SJ thought he might cry. “Jesus,” he said. “You gotta talk to my lawyer. He’ll listen. You’re . . .” He looked SJ up and down. “Christ, you gotta talk with him.”

“What did your lawyer say?”

Mickey, standing there in his garage: “What if he wanted it?”

“It shouldn’t matter if he believes me, right? Lawyers, that’s their job, to defend you no matter what,” Mickey said.

The visiting room was overheated. SJ pushed up the sleeves of her sweater. The room buzzed with conversations, an occasional laugh. She noticed the man with the white eyebrows talking to a young man who might be his son. The man looked so defeated; the son, his dark eyes hard, mouth set. SJ thought of Mrs. Gilberto, the way hope alternated with despair, so you could see it in her eyes, hear the hope slip into her voice then cut out. She saw again the way she had clasped her purse, keeping the hope bottled up, the pride too, but wanting, wanting more than she ever wanted anything before to release them and so convince SJ that her son was someone worth saving, still worth loving.

“You gotta believe me. I . . . didn’t . . .”

“Mickey, not here.” She put up her hand. “Stop. It’s okay.”

“You’ll talk to him then?” He leaned forward. Cuffs clinked.

SJ felt the damp hair at the nape of her neck. She couldn’t promise more than she was able to do. “Listen. I—I just don’t think there’s anything I can do . . . I’m not sure I’m the one . . .” Her voice drifted off. It was so strange, this speaking on a phone to someone just in front of you.

“Just talk to him. Just—that’s it. “ He rubbed his hands on his thighs. “I need you to do this.” His voice, carefully monitored, calibrated. SJ heard it then, the insincerity, the tone a subtle shift, a deliberate ploy to get SJ to do what he wanted. What if he wanted it? Mickey shook his head. “This is some crazy shit,” he muttered, the tone gone now, his own voice back.

SJ saw herself then, showing up at Mickey’s garage, remembered the drive that night, the horrible

kiss.

Mr. Freeman.

“Your mother,” SJ said, one arm folded in front, “she’s pretty worried about you.”

Mickey’s gaze shifted again. She couldn’t detect whether there was any honesty or sincerity there. He shrugged. “She’s a tough lady. She’s been through worse.”

Worse. What could be worse than your son in prison for rape and murder? SJ tried to swallow. She had been so certain of his innocence. And she had promised his mother. But what could she do, really? How had she let things go this far?

He smiled crookedly. A smirk. “You should ask your girlfriend what it’s like in this hellhole. Ask her how they treat people like us.”

People like us. SJ had to fight the urge to leap and say, She’s not like you! She’s nothing like you! She blinked. It was so hot. She wiped at her brow.

Mickey laughed a mean little laugh. “Even me, stuck in solitary, I heard about her. She tell you I saw her? Talked with her?”

SJ felt the heat rise to her face. Deirdre hadn’t said much about her time in jail—a few comments about the other women, several prostitutes and others, caught dealing or using drugs. She hadn’t said anything about Mickey. And SJ had asked few questions. They both seemed to think that the less they talked about it, the less real it might seem. She stammered, “Look, I’m sorry. I’ve got to go.”

It was a fatal mistake to bring Deirdre into the discussion. Mickey gestured with his cuffed hands. “Yeah you know, what the fuck?” he said. “And thanks for nothing.”

“I’m sorry,” SJ said again. “I . . . I’m sorry.” She hung up and hurried out of the room.

* * *

In the car, SJ fumbled with her keys and let the tears fall. How could she have thought him innocent? She felt dirty suddenly, the kiss a sordid memory, a terrible mistake that would forever tie her to Mickey Gilberto, child molester and murderer. She started the car, the tears a torrent now. She rubbed the snot from her nose on her sweater sleeve and turned off the radio so she could focus on the drive. What had Deirdre said—If you’re staying but you want to leave, you can? Was that it? It should be clear, shouldn’t it, whether or not she wanted to stay or leave, but it seemed the murkiest thing to her. Her brain was like a mud puddle. She thought she had genuinely cared about Mickey. She thought she had wanted to help him. And now her muddled brain seemed to be telling her something else; it seemed to be saying that maybe—she hated to admit it—but maybe her initial impulse to help Mickey had been about something else altogether. She remembered him walking into the library, looking for literacy classes, and the way she eagerly agreed to teach him. She remembered feeling him next to her, the faint smell of his cologne and watching the way he concentrated on forming each word. In those moments, she had felt sure that she understood him. She’d felt committed to helping him learn to read.

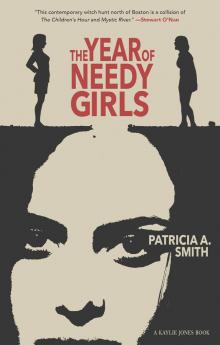

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls