- Home

- Patricia A. Smith

The Year of Needy Girls Page 27

The Year of Needy Girls Read online

Page 27

The door opened and shut. “Hey, hon!” The smell of outside wafted in, fresh and bright.

“We’re in here,” Deirdre called.

SJ stepped into the living room, cheeks pink from the cold. She kissed Deirdre on the cheek.

“You’re home early,” Deirdre said. She felt herself blushing, as if she had been caught doing something wrong. “I don’t think you’ve met Beth Ann yet, Ellie’s mom? You’ve heard me talk about Ellie.”

“Of course.” SJ and Beth Ann shook hands.

“So Beth Ann had some news—”

SJ stopped.

“She was telling me there are more accusations.” Deirdre twisted around from where she sat on the couch.

“What?” SJ turned pale.

Beth Ann strode across the room and picked up her purse. “No one is taking them seriously. Not even Martin.” She wrapped a black scarf around her neck. “Listen, I’ve got to go.” To Deirdre she said, “Keep me posted, will you? And I’ll do the same.”

As Beth Ann left the house, SJ took off her jacket and walked to the bedroom. “Tell me about these accusations. Shouldn’t we be worried?”

“I am worried. A little. But Beth Ann says that seriously, Martin thinks they’re ridiculous—”

“But why make them in the first place? What’s that about?” SJ interrupted as she emerged from the bedroom.

“I thought the same thing.”

“What if they get on the stand and say that you’ve . . . What are they saying exactly?”

“I don’t know—that I kissed them, I think? Multiple times, even! It’s ridiculous when I think about it.”

“Well, let’s hope a jury or a judge thinks so too.”

“The thing is, don’t those girls know they’re playing with my life here?”

“Oh good. I’m glad to see you are taking this seriously!” SJ flopped onto the couch.

“Of course I am, but . . . I just don’t even know what to think anymore. Or what to do.” She snuggled up against SJ. “For now, let’s just not think about it, okay? Maybe it’ll all go away.”

“A questionable defense strategy, but for now . . .” SJ kissed Deirdre on the top of her head.

* * *

Beth Ann’s visit, unexpected, had jolted Deirdre, not altogether unwelcome but not altogether pleasant, either. Her days had become small, just her and SJ and what little routine they had together. In the weeks since her arrest, her old life—and that’s how Deirdre thought of it—her old life already seemed remote. Three months into the school year, the seniors would be freaking out about college applications, panicked about essays, and looking for reassurance, hounding their favorite teachers for recommendation letters. Deirdre normally had upward of fifteen or twenty to write and she wondered who would take up the slack. The new students would be settled in by now, feeling at home, no longer awkward about participating in school traditions, singing the alma mater as if they’d known it all their lives; no longer having to peek at the cheat sheet they kept jammed in their pockets for the Friday assemblies; calling the teachers by the inevitable nicknames passed down from class to class; teachers would be excited about the upcoming Thanksgiving break, eager for the first real vacation from the franticness that is back-to-school. Though truthfully, the beginning of the holidays didn’t really give anyone much rest, not until Christmas—and there would be the knowing looks from one teacher to another. Hang on, they would say. It won’t be too long now. Even Beth Ann seemed no longer new to town, to the school. She had talked about Brandywine as if she’d been part of it for years.

Just thinking about it all exhausted Deirdre. Part of her wanted to see the girls, or at least let them know she was thinking about them, wondering how they were doing without her. Part of her envied Madame Delambre, forging relationships with the students, becoming their new connection to French and the French-speaking world. And some part of her wanted to forget that she had taught at Brandywine, or that she’d ever taught at all. Just seeing Beth Ann had brought the girls’ neediness right into the house, and where once Deirdre might have been exhilarated by it, now she felt a mixture of anxiety, fatigue, and still, yes, a jolt of adrenaline. It was tricky, this business of being needed. Deirdre had been unaware of it in such an intense way until now, and she wondered how much being needed had fueled SJ’s desire to help Mickey Gilberto. She wanted to talk with SJ about all that, but at the same time, she couldn’t. She couldn’t bring herself to even mention Mickey Gilberto’s name. They still had not talked about Deirdre’s adventure in Provincetown, either, and both of those topics hovered in the air, a palpable heaviness. Maybe they might not ever talk about them. Couldn’t she and SJ forge ahead and create a new, longer-lasting relationship? Couldn’t they make this thing work together? At the moment, it felt like they could, and that was enough for Deirdre.

Chapter Five

And suddenly, in early November, Anna Worthington recanted.

She came downstairs and announced that no, Ms. Murphy hadn’t “gone after her,” hadn’t made her feel uncomfortable, groped or touched her, hadn’t been inappropriate with her in any way.

“But I saw the two of you kissing,” her mother said.

“You thought you saw,” Anna insisted. She was tired of being left out at school, of the other girls insisting that they, too, had kissed—or had been kissed by—Ms. Murphy. They were saying it, Anna was sure, to make fun of her, to show the school how silly it was to believe her story, how it couldn’t be true if all of them were saying it.

“I know what I saw.” Her mother wouldn’t back down.

“What you saw—” Anna spun around to face her mother at the kitchen island, “was me kissing her, okay? I kissed her. That’s the way it went.”

Her mother sputtered, “It . . . it’s inappropriate . . . it’s her fault . . .”

“Oh for God’s sake, Mother! Stop it. Just stop it. This whole thing is out of control. I did it. Have me kicked out of Brandywine, why don’t you?” And she stormed off to her room.

For a long while, Anna had believed her mother when she said that everything that happened was Ms. Murphy’s fault. She believed it when her mother said that Ms. Murphy had crossed the line with all the girls. “I’m not surprised,” her mother had said when they heard about the other, more recent accusations. “There will be more, mark my words.”

“You think she was after us?” Anna had asked back when they were first discussing the “incident in the van.”

“Homosexuals are known predators,” her mother had said. “They have to convert children. I know it sounds silly, but that’s what they do.”

“So you think she deliberately set out to . . . to brainwash us? Get us to . . .” and Anna had paused for a second, felt herself blush, “fall in love with her?”

“In a manner of speaking, yes. I think that’s exactly what she did.”

At first, Anna wanted to believe it. She wanted to think she had no control over how she felt, that it was a spell that made her feel crush-y and lightheaded and like she never wanted to leave Ms. Murphy’s room. She didn’t want to acknowledge that it might be her. So she found herself thinking about her mother’s words and wondered if it might really be a good idea to prevent gay people from teaching. Hadn’t life been easier when Hilary, Lydia, and she spent their time looking for dresses for the sophomore semiformal, wondering who to ask from among the St. Michael’s boys they knew?

When the girls first approached her about getting Ms. Murphy in trouble, she stood her ground. “It’s not my fault,” she told them. “She doesn’t belong here. She’s affecting all of us.”

Lydia had spoken up immediately: “Oh my God, you’re ridiculous!”

Hilary had grabbed Lydia’s arm. “See? I told you. Forget it.” She pulled Lydia to leave.

Only Morgan Abernathy had listened with any real interest.

And Morgan was the only one still by her side.

Now, here it was, close to Thanksgiving break, and Anna ha

d never felt lonelier. She’d spent hours and hours going over it, trying to remember if Ms. Murphy had ever, even slightly, encouraged her, had ever let Anna think that she had thought of her as something other than one of her French students. Anna replayed those early weeks of school, all the minutes that led up to the final one, when she found herself alone in the van with her favorite teacher, a woman who took up much of her imagination, and Anna had somehow found the courage to kiss her.

* * *

When the charges were dropped, the Boston Globe featured the story on page one of the Metro section and the Register had it right there on the front page.

One day later, Lydia called Anna. “Hey,” she said. “Saw the news. That’s cool. But what happened?”

Anna blinked back tears. “I guess it wasn’t really her fault, you know?”

“Too bad she got fired though, huh?”

Anna couldn’t hear any particular tone in Lydia’s voice, just a kind of tiredness or sadness. “Yeah. I think what’s done is done though. That’s what my mother says.”

At that, Anna was certain she heard Lydia hesitate. “You know she’s moving? Hilary heard she’s moving to P-town. Guess she’ll be happier.”

“Do you think she’ll teach there?” Anna asked in a quiet voice.

“Dunno,” Lydia said. “I doubt it.”

“Yeah.” Anna took a deep breath and sighed. She couldn’t help it. The tears fell. “I’m really sorry.”

“I know,” Lydia said.

They made tentative plans to hang out over Thanksgiving.

“Maybe a movie or something?” Lydia suggested.

“I didn’t mean to ruin everything,” Anna said, blowing her nose. “But I did, didn’t I?”

“The others will come around. Hilary will come around. It’ll be okay.”

Chapter Six

Fear still permeated the air in Bradley. Worse now that the bright sunshine seemed to be permanently gone, replaced with gray skies and that cold, piercing wind. Mickey Gilberto still had not been brought to trial, but he had been formally charged. The Globe reported another man too, someone the article alleged had done the actual killing, an older man, someone Mickey had met in a chat room. The Register reported accusations back and forth, each man insisting the other was mainly responsible. The fact that both men had been apprehended might have been enough to put people’s minds at ease but still somehow an uneasy tension lingered. You could feel it woven through conversations, an invisible string linking everyone together. SJ thought of it like an old house, a stately Victorian, nicely painted and detailed, but, on closer inspection, in desperate need of updating, with its peeling ceilings and drafty windows, hidden pipes leaky with terrible plumbing. It was hard to tell whether folks felt scared for their children—it wasn’t as if fewer children appeared out of doors, or the after-school kids stopped coming to the library, though SJ did feel a kind of distance from a few of the parents who picked them up—real or imagined, she couldn’t say. There was no way to determine what they knew; if, for example, they knew that SJ had been teaching Mickey Gilberto to read, and so therefore was contaminated by close proximity, or whether they knew that Deirdre-Murphy-the-child-molester-teacher was her partner.

SJ felt branded with an expiration date, past due. “I think we need to move,” she had said to Deirdre, and then realized what that meant, what she was suggesting.

She watched the hope on Deirdre’s face, heard the careful monitoring of that hope in her voice when she answered: “But I love this house, don’t you?” And then, “I’m open to it. Let’s see.”

Gone, at least, the leaden weight of the arrest and looming trial. Those days had gaped with uncertainty, great yawning crevasses that made you want to leap off the edge. The town meeting over which everyone was still arguing; the endless letters to the editor, some even now still appearing like out-of-season Christmas cards, the sentiments sincere-sounding but so long after the fact that you wondered, Why bother? What was the sense in doing it now, except to jump on the bandwagon? The conversation had changed; the charges had been dropped.

Of course, for SJ and Deirdre, things were far from settled. Deirdre still didn’t have a job. And SJ still had the apartment; she had to make a definitive decision—break the lease, sublet, or something else. Deirdre had not yet divulged details about her little escape to Provincetown. And for her part, SJ certainly had said nothing about seeing Mickey at his garage, and nothing about the kiss. So there were definitely things to be worked out. If they could be worked out.

A fog had settled over Bradley, a brooding gray that was the result of the weather, yes, but also of this other constant element—fear, nervousness, distrust. SJ likened it to Puritan times, the way she had felt as a kid reading about them. She remembered now the glum feeling she had experienced, curled on the couch in the Marblehead house or in bed with the comforter pulled up to her chin, reading those books for her English classes. She remembered the unshakable feeling of doom and sadness; she had wondered then how the Puritans could be the precursors for so much that Americans, or at least New Englanders, took for granted—the work ethic, town meetings, and education. She remembered how gray everything had been in her imagination, how the characters seemed to move through their lives in a slow shuffle. Funny that now, walking around Bradley, SJ saw the town through the same pallor and she could swear her legs felt weighted down, however bright her daydreams.

In the East End, things were a bit different. There, the feeling was one mostly of sadness, palpable and with its own particular weight, but less gray, less accusatory. This part of town had endured so much loss, though still the kids played outside at recess at Most Precious Blood, and still the boys shot hoops in the park, and still girls strolled to the corner store and giggled with their girlfriends. There was still Bingo on Wednesday nights in the church hall, still buyers for lottery tickets, still boys careening on their BMX bikes and skateboards. But to SJ at least, all of this went on as if under a veil, thinly layered and ever present.

At work, the other librarians and staff gave SJ a wide berth. Elliot chatted with her less frequently or went out of his way to find Florence when normally he would come to SJ with questions. Florence remained her steadfast self, but even she seemed less inclined to hang out with SJ during lunch break or linger over morning coffee as they used to.

On this day, SJ cornered her. “Florence . . .”

She looked startled, surprised to hear SJ’s voice, see her standing so close to the photocopy machine. “Sara Jane . . . hello.” Florence adjusted her scrimshaw. She was wearing a new silk blouse, one that SJ hadn’t seen before.

“You’re avoiding me.” SJ crossed her arms.

Florence flipped through the papers she held in one hand. “I’ve been busy. You know that.”

“Busy,” SJ nodded. “But that’s just an excuse, isn’t it?”

Florence blushed. “I thought you might need your space, a little time. I didn’t want to intrude.” She shifted the pile of papers. “I’m glad—it’s good that the charges have been dropped, isn’t it? That must be a huge relief. I’m happy. For you both.” She started to walk away.

SJ wanted to grab her; she half-wished Florence would give her a hug. “You were right about Mickey Gilbero,” she blurted.

Florence turned and gave a little smile. “I’m just glad things are settled.” She walked back toward her office, heels clicking on the floor.

* * *

Sometime that afternoon, after Florence and Elliot and the others had left the library, after the streetlights had come on and the dark had overtaken everything, SJ found herself sitting in her office, at her desk, looking again at the picture of Deirdre taken on the Cape. She saw again someone she would hardly recognize now, a version of Deirdre she hadn’t seen in years. And somehow, in that beach memory that was preserved in the way that photographs have of turning the past into a kind of lie, SJ was catapulted back to Marblehead, to the landscape of her youth, a place she visited r

arely now and viewed only through a grainy and safe distance.

Early in their relationship, Deirdre had insisted that they were both boat people and therefore destined to be together. And while it was true that Gloucester and Marblehead share a coastline and that thick New England air, Gloucester’s harbor is full of fishing vessels and lobster boats, while Marblehead’s is panoramic, a distinguished collection of leisure crafts—lovely wooden and fiberglass sailboats, several yachts, a schooner or two.

SJ had laughed. “I’ve never been on a boat.”

“From Marblehead and you’ve never been on a boat?”

“Nope. Didn’t own one. Didn’t know anyone who owned one.”

“How is that even possible?” Deirdre had said. “Isn’t that like living in Maine but never eating lobster?”

But SJ had just smiled. “I’m sure there are Mainers who are allergic.”

“Okay, but boats . . . you can’t be allergic to boats.”

“We just didn’t know anyone who had one. It’s not that strange.”

Still, Deirdre maintained that boats were their common denominator. “There’s something about growing up around them. I don’t know. It’s silly maybe. I just think there are things we’ll immediately get about each other.”

But growing up around boats had meant for Deirdre a rough-soled existence, all salty sand and mist. Not so for SJ. Her growing up had been the country club and polo shirts. She didn’t have that same feeling about the coastline as Deirdre, no matter how much Deirdre insisted she did.

“I’m sorry to disappoint you,” SJ had insisted, “I simply don’t have that love of the ocean that you do.”

Deirdre couldn’t be dissuaded. “It’s there. You’ve just buried it deep.”

At first, SJ found Deirdre’s certainty amusing. She would laugh. “Whatever you say. I’ve buried it deep.” But after some time together, SJ didn’t understand why Deirdre couldn’t see that she had been wrong. Even after knowing SJ, hearing about her childhood, meeting her parents and visiting their home, experiencing its austerity and lack of warmth—still, she had insisted they shared a common culture and love.

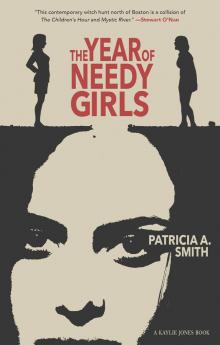

The Year of Needy Girls

The Year of Needy Girls